![]() By 1918, as America entered the First World War, the political and military consensus was that African American soldiers would not fight alongside white soldiers in combat. Although American soldiers of color were ready to fight and die for their country, many who would serve under an American flag would be relegated to supporting roles and labor regiments. The French however, had no misgivings about utilizing black troops. Allied American and French commanders agreed that segregated black regiments would fight with the French Army under the command of French commanding officers. American citizens and soldiers of African heritage would face German bullets, tanks, machine guns and gas fighting for their country under foreign command. The true irony of intolerance.

By 1918, as America entered the First World War, the political and military consensus was that African American soldiers would not fight alongside white soldiers in combat. Although American soldiers of color were ready to fight and die for their country, many who would serve under an American flag would be relegated to supporting roles and labor regiments. The French however, had no misgivings about utilizing black troops. Allied American and French commanders agreed that segregated black regiments would fight with the French Army under the command of French commanding officers. American citizens and soldiers of African heritage would face German bullets, tanks, machine guns and gas fighting for their country under foreign command. The true irony of intolerance.

Despite the prejudices of the 19th century spilling over into the start of the 20th century and WWI, African American men came forward to serve their country, and more importantly, seize an opportunity to gain respect and equality. The first African American division to arrive for combat in France was the 93rd Infantry Division and their four regiments. This is the story of one soldier and his regiment that reflects the lives of the thousands of African American men who were willing to serve, fight and possibly die for a country that was not ready to recognize them as equal citizens.

My maternal, great uncle, 1st Lt. Charles Henry Barclay served with the 372nd Infantry Regiment during the Great War. The 372nd was an African American regiment, a part of the 93rd Infantry Division (Colored), that served with the French Army during the final year of war. The 372nd included the First Separate Company of Connecticut, largely National Guard troops, that included my great uncle as an officer from New Haven. He would serve in France between March, 1918 and February, 1919 and was wounded by mustard gas during the Battle of Argonne Forrest.

Quiet Years Before the Storm

Charles Henry Barclay was born in 1873 in Bridgeport, Connecticut to a prosperous family. His father, Charles Thomas Barclay, was an accountant who also operated several profitable barbershop businesses. The Barclay family traces itself as free African Americans back to 18th century Philadelphia. The Barclay family lived in the “Little Liberia” section of Bridgeport that during the mid-19th century would become one of the most important free families of color communities in America. He married in 1896 and he and his family moved to New Haven by 1903. He operated his own ornamental sign painting business at 102 Ashmun Street and he would frequently visit and entertain his brother George Nicolas Barclay’s family from Newport, RI, another major enclave for New England African American families of education and means.

New York Age Newspaper March 14, 1907

Regiments of Color

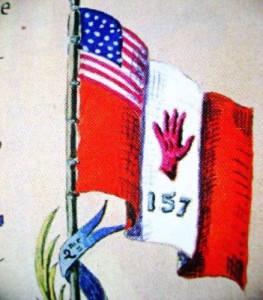

At the age of 45 when most men stayed comfortably behind, Lt. Barclay and the 372nd departed on March 30, 1918 from Newport News, Virginia aboard the U.S.S. Susquehanna, arriving at St. Nazaire, France on April 13, 1918. The French Army, whose front-line troops were devastated from nearly four years of largely trench warfare, requested and received control of several regiments of black combat troops. The 372nd and three other African American regiments including the 369th, 370th, and 371st within the 93rd Division and were combined within a new French Combat Division. They would serve under the command of French General Mariano Goybet and the newly constituted 157th French Division. The soldiers were issued French rations, equipment, the distinctive French helmet, and the “Red Hand” patch to wear on their uniforms.

Battle of the Argonne Forrest

French 157th “Red Hand” Division

On September 26th three regiments of the 93rd American Division were ordered to attack from a position a few miles west of the Argonne Forest. On the 28th of September the 371st and the 372nd Infantry entered the lines as part of the Red Hand Division and attacked at once, advancing through murderous gunfire and gas. On October 1st the 372nd relieved the 371st and advanced to a point near the Monthois Township where it was subjected to raking gunfire. It held this position until the night of the 6th. A few days later all three of the regiments, having won the praise of the French officers for their conduct in the attack, joined other French divisions for the push through the Vosges region of Eastern France to the very doorstep to Germany.

Aftermath

On the 11th of November 1918 an armistice between the Allies and Central Powers was reached ending the Great War. Lt. Charles Barclay survived the war, recovering from effects of mustard gas and returning to his family and sign painting business in 1919. Like nearly all of the African American combat veterans that returned to America after the war, Barclay would start life afresh with the expectation that his service would contribute in some small part to creating a better world and better America. As the troops of color returned to their home towns, cities and states with high expectations of equality, employment and respect, in its place they faced an unprecedented increase in racial tensions across America that led to the eruption of race riots across two dozen cities during the summer of 1919, which historians today refer to as “The Red Summer.” Tragically, the lynching of African Americans would also rise like no other time since the Jim Crow days of the late 19th century. Some African American veterans would be lynched while in uniform. As a direct outcome of the First World War and the aftermath of the treatment of veterans returning home, African Americans became increasingly politically active in their struggle against racial discrimination, led by organizations such as the NAACP founded in 1909. It would take a Second World War and years of civil rights law enactments to bring America in line with its founding principles that “All men are created equal.” And it would be the African American citizen soldiers like Charles Henry Barclay, who would be willing to fight and possibly die for a country at a time when there were no guarantees for full citizenship, which would best exemplify American equality and freedom.

- From Enslavement to Entitlement - June 11, 2020

- Rhode Island African Heritage & History Timeline: 17th through 19th Centuries - January 21, 2016

- A Woman of Valor - October 3, 2014

Click on image to view pdf

Click on image to view pdf

March 17, 2015 at 5:40 pm

Thank you for a rarely heard of account of Regiments of Color and the aftermath of their return to American soil. My Great Grandfather served as Sergeant for the 371st/ Machine Gun Company, and was honorably discharged from being gassed in the Battle of the Argonne Forrest, possibly alongside your great uncle, Lt. Charles Barclay. I stumbled on Great Grandpa Sgt. James J. Foster Jr.’s service while researching my family tree and now understand why some veterans don’t speak of their military lives. I’m honored to be a voice for him and his military brothers by sharing their story, as you did with this blog post. Thank you!

March 1, 2016 at 5:20 pm

I’ve found each post most informative. Thanks! I’m Barbados’ Honorary Consul to SC and the Founder/CEO of the Barbados and the Carolinas Legacy Foundation. The historical links between Barbados and Carolina have been well researched and documented. In historical circles Barbados is seen as the colony where the horrendous system/policies that supported plantation systems in the Caribbean and North America (colonial South) were birthed then transported to other places. People, whether free or enslaved, white or black, were a part of that story. This brings me to the “Barclay” family from Barbados who left their indelible stamp on Liberia. Barbados views the history of the “Barclay” family as part of its own history where migration to other larger countries was necessary because of its size and want of natural resources. Is your family connected in anyway with the Barbados Barclays? I’d be delighted with a response. Thanks for your consideration.