Over two years after January 6, 2021, as our nation continues to recover from the violence and insurrection directed at our nation’s capital, led by many who carried our American flag, I am reminded of my Richmond, VA-born great-grandfather, Richard Gill Forrester. At the tender age of 13, in unselfish patriotism, he rescued the flag from Confederate insurrectionists at the start of the Civil War. It is more than ironic that a young man of mixed racial heritage and Jewish faith would perform a deed of patriotism at a time when America was deeply divided by race, religion, and war. My great-grandfather’s heroic actions have helped me understand the American flag’s significance and why it continues to symbolize hope for all Americans. For that reason, I want to share his story.

Virginia ratified the ordinance of secession on May 23, 1861. Shortly after, the newly constituted Confederate Congress declared Richmond as the new headquarters of the Confederate States of America. The announcement drew wild celebration on the capitol grounds with thousands of rebel revelers.

Members of the crowd tore the national flag from the top of the capitol building, threw it into a rubbish pile, and planned to burn it in a bonfire. Forrester, a page at the capitol, amid the chaos of celebration, rolled the flag into a bundle and carried it to his home a short distance away on College Street.

Once there, unknown to his own family, he placed the flag under his bedding, where he slept on it nightly for the entire four years of the war. The risk he took, rescuing and preserving what was seen by nearly all Southerners as the symbol of Northern aggression and invasion, was significant.

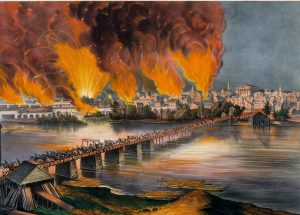

On the morning of April 3, 1865, after four long years of bloodshed, Southern soldiers, officials, and sympathizers abandoned Richmond to the advancing Union forces. In all the fire, smoke, and confusion, Richard dashed onto the capitol grounds and up the spiral staircase leading to the roof. There, he replaced Old Glory before the arriving Union troops. One of the first of many Union troops to enter Richmond included a company of men with the Thirteenth New Hampshire Regiment. The regimental memoirs were compiled and published as “Thirteenth Regiment of the New Hampshire Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion” by S. Millet Thompson, an officer with the regiment. Thompson provides a vivid and detailed account of the events of the fall of the Confederate capitol:

“There was no flag on the roof of the capitol when I entered the grounds, but within a few minutes it suddenly appeared on the flagstaff on the roof, and immediately afterward I had a conversation with the man who raised it. He was a light-colored boy named Richard G. Forrester,

living on the corner of College and Marshall. When the State of Virginia passed the ordinance of secession, he was a page or errand boy employed in the capitol.

The secessionists tore down the flag and threw it among some rubbish in the eaves at the top of the building. At the first convenient opportunity, he rolled the flag in a bundle, carried it to his home and placed it in his bed, where he slept on it nightly since that time. This morning, he said, as soon as he dared after the Confederates had left the city, he drew the old flag from its hiding place, ran to the capitol with it, mounted to the top and ran the flag up the flagstaff. This was the first flag hoisted in Richmond after its evacuation by the Confederates.”

After the war, Forrester moved north to New York City with his young family. Taking a job with the New York and New Haven Railroad, he summered in Newport, Rhode Island, the historic home of his Jewish ancestors and where his beloved Richmond family members who helped raise him were buried. He lived a full and active life and was laid to rest at the historic Island Cemetery in Newport on November 15, 1909, with military honors by the Lawton and Warren Post No. 5 of the Grand Army of the Republic. Thirteenth New Hampshire Regiment veterans assisted in his burial and honored him as a soldier for his heroic deed.

Today, Old Glory is proudly displayed, fluttering on front porches, unfurled over our brave veterans’ burial markers. People wrap themselves with the flag as a symbol of protest or when declaring themselves the only true patriots. Many believe we live in a divided nation, with many Americans attaching our country’s flag to their own agendas, begging the question, what does patriotism really mean in America?

My ancestors served in nearly all of our country’s wars, beginning with the American Revolution. Indigenous, Black, and mixed racial heritage men and women believed in serving their country, even when denied the most basic rights of full citizenship. Richard Forrester, then a teenager, embodied their beliefs they were Americans. They believed that, while not perfect, our country still held the opportunity for them to be recognized under the fundamental principles of our democracy with all the rights and privileges of being American. During one of America’s most tumultuous times, a young Richard Forrester expressed one of the most extraordinary acts of patriotism by safeguarding the symbol of that belief – our American flag.

- Saving Old Glory - March 31, 2023

- Keith Stokes receives Outstanding Achievement in Leadership Award - December 22, 2022

- Harriet Jacobs - December 22, 2022

Click on image to view pdf

Click on image to view pdf

Leave a Reply