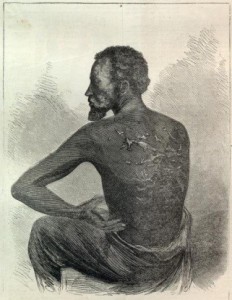

Image: Harper’s Weekly, July 4, 1863

The September 27, 1856 edition of the Richmond Times Dispatch ran what might have been for most readers at the time an amusing story concerning stolen chickens from the farm of one of the city’s prominent citizens. The news story describes a slave named Brittan belonging to a George Turner being under arrest and sentenced in the Mayor’s Court for the theft of a number of valuable hens from Richard Forrester’s farm. The article (extracted) entitled, “A Chicken Fancier” dripped with sarcasm and amusement as it described:

“During the small hours of Thursday morning, say about 3 o’clock, he (Forrester) heard some person enter the hen house, where he was concealed, on the watch. The intruder, believing the coast was clear, lighted a match, illuminating the humble abode of the feathered family to such an extent that Forrester saw and recognized the prisoner, Brittan. A bag of feathers, evidently plucked very lately from the defunct hens, was found on Thursday in Brittan’s room. The Mayor booked him for 30 lashes, which may possibly teach him a lesson in good morals. This Negro was arrested last year, on a similar charge. His affection for chickens is really unaccountable.”

– Richmond Times Dispatch, September 27, 1856

Flogging was a common form of discipline and punishment for slaves. It was generally carried out during the period before the Civil War and particularly on plantations and urban slave centers such as Richmond, Virginia. With almost certainty, most white Richmond citizens of the time would not have seen whipping slaves to be in any way harsh or unfair, but perhaps essential to upholding the law and order of a society comprised of slaves and masters. In his autobiography, former Richmond slave Louis Hughes vividly recounts:

“Whipping was done at these (Richmond) markets, or trader’s yards, all the time. People who lived in the city of Richmond would send their slaves here for punishment. When any one wanted a slave whipped he would send a note to that effect with the servant to the trader. Any petty offense on the part of a slave was sufficient to subject the offender to this brutal treatment.”

– “From Bondage To Freedom”, Autobiography of Louis Hughes, 1897

But on that September evening back in 1856, what would have been going through the mind of Forrester, a free person of color and evidently prosperous Richmond resident, who was himself only a couple generations removed from the very same slave system that Brittan (who might have taken the chickens to simply feed himself and other slaves) was now an unfortunate participant? Forrester, who at the time had a growing family with a wife and ten children must have known that after Brittan was apprehended, his punishment would have been to endure the pure agony of the lash? But what risks would he have taken against self, family and property if he had spoken up and in contradiction of Brittan’s punishment years before universal black emancipation and freedom?

While the fate and future life of Brittan is possibly lost to antiquity, it is more than ironic the man he stole from would later become a leader in upholding human and civil rights for newly freed slaves in post-Civil War Richmond. Richard Gustavus Forrester was living at the property he owned at the corners of College and Marshall Streets, above Schockoe Valley where he operated a successful dairy and chicken farm, frequently advertising the sale of rare, “Shanghai and Chittangong” hens along with other dairy foodstuffs. The brutal consequences of Brittan’s actions may have influenced Forrester as a forerunner to the struggles for racial equality that later Virginia and all of America would face after the Civil War. During Southern Reconstruction Forrester would become the first man of color to be elected to both the city council and school board, where he led efforts to guarantee equal representation before judicial systems, ensuring that all persons of color were afforded the benefits of citizenship, adequate funding of black schools and hiring of black teachers.

This story is a sobering example of the complexities of American slavery. A system where, by 1860, Virginia would have America’s largest population of enslaved African Americans – over 500,000; but also nearly 60,000 free persons of color, with most living in Richmond. The interaction between these populations of color were greatly complicated by the wide-ranging “Negro Codes” of the time that not only governed the life of slaves, but also set strict standards of conduct and daily living for freedmen. For the very essence of slavery is one human-being controlling another, and capital punishment led by whippings was deployed as a very effective means to maintain control. Maybe our late, great 16th President understood how to best understand this “peculiar” institution:

“Whenever I hear anyone arguing for slavery, I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.”

– Abraham Lincoln

-KS

- Saving Old Glory - March 31, 2023

- Keith Stokes receives Outstanding Achievement in Leadership Award - December 22, 2022

- Harriet Jacobs - December 22, 2022

Click on image to view pdf

Click on image to view pdf

September 27, 2015 at 4:28 pm

Bless your family for their fortitude n sacrifice in these stories of knowledge for history.

July 2, 2016 at 3:42 am

Great story about whipping history. My Great grandmother was Celia Adams, born March 12, 1856-March 21, 1943. She was sold from Richmond, Virginia to Louisville, Georgia. This area had a reputation of maintaining public whipping posts during the pre-Civil War period. Read accounts of the era in my book titled, The Legacy of Celia Adams: From Slavery to Freedom.–JH