The year 2020 marks the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution that enacted the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This year is also highlighted by the United States elections to be held on 3rd Tuesday in November. Along with the election of the President, all 435 Congressional seats and 35 of the 100 Senate seats will be contested.

The 15th Amendment’s adoption was met with widespread celebrations  within African heritage communities across the country. It also launched an era of insidious attacks on free speech and representative government with poll taxes and literacy tests instituted across the American South, effectively disenfranchising the great majority of voters of color. The irony that the South was instituting literacy tests for people who, just a few years before, were barred from learning to read by law was not lost. In many cases, these voting restrictions were brutally enforced by the newly organized Ku Klux Klan. The Klan led attacks included beatings and lynchings of African heritage voters as a means of keeping them from the polls. These vicious attacks would continue well into the 20th century.

within African heritage communities across the country. It also launched an era of insidious attacks on free speech and representative government with poll taxes and literacy tests instituted across the American South, effectively disenfranchising the great majority of voters of color. The irony that the South was instituting literacy tests for people who, just a few years before, were barred from learning to read by law was not lost. In many cases, these voting restrictions were brutally enforced by the newly organized Ku Klux Klan. The Klan led attacks included beatings and lynchings of African heritage voters as a means of keeping them from the polls. These vicious attacks would continue well into the 20th century.

The freedom to vote may very well be America’s most important civil right, and for the African heritage community in particular, it is also the most hard-won right. We know this because American history is filled with documented accounts of highly organized and legal voter restriction and suppression against the African heritage community. In addition, the struggle many African heritage men suffered through to exercise their right to vote paved the way for all those who came after, most notably the Women’s Suffrage Movement and immigrant citizens.

One hundred and fifty years ago, America had entered a major turning point in its history. The Civil War was over, Reconstruction and the new era of African heritage Civil Rights was at its peak, and Congress had recently passed the 15th Amendment. As someone whose ancestors date back to the early formation of America, and not always looking like, worshipping like, living like and fitting neatly into what history books would commonly refer to as the early American experience, I have to depend upon my own ancestral accounts to help me understand what America was like for people representing minority racial, religious, and ethnic history. In my case, I am thankful to have many primary documents and heirlooms that recount my American story, and unfortunately, from a perspective that far too many history books have omitted.

During the era of the 15th Amendment, two of my ancestors would play unique and historic roles in advancing the importance of voter registration and participation as a vital aspect of building political power within the African heritage community of early America.

One ancestor was a man of color who lived as a free man before, during and after the Civil War in Richmond, Virginia, the once Capital of the Confederacy. Another ancestor would relocate his family from Richmond to Wisconsin in 1858 and establish himself as an early settler, business leader and perhaps the first lawful voter of color before the adoption of the 15th Amendment.

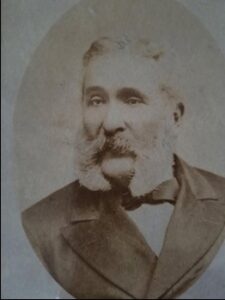

Richard Gustavus Forrester

In Richmond, my maternal great, great grandfather Richard Gustavus Forrester would become a successful business and political leader serving as the first man of color on the Richmond city council and school board leading the efforts to promote equal opportunity and access for all newly emancipated African Americans immediately after the Civil War.

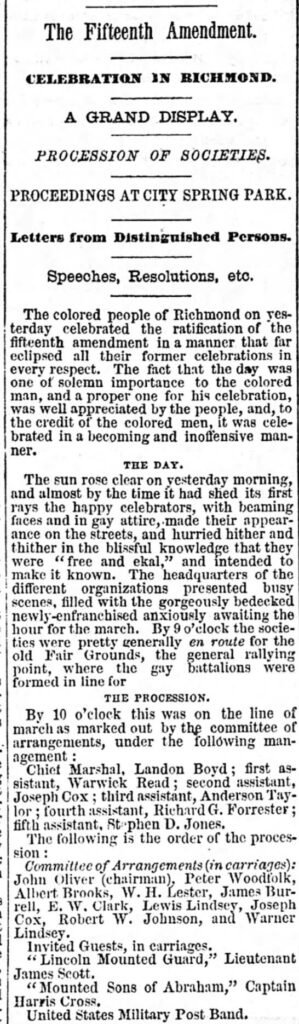

On April 21, 1870, Forrester was a leader in organizing one of the nation’s earliest and largest celebrations of the ratification of the 15th Amendment with a grand event symbolically held within the fallen Confederate Capital of Richmond. Thousands of marchers representing African heritage religious, civic and political organizations from across the state took part in a display of pride in achieving what was their inalienable right as full citizens of their America.

Richard Forrester and others in 19th century America were keenly aware that voting rights provided the African heritage community not only the freedom to choose their government leaders but to build political power within their community and create real change for those who were once enslaved within the “land of the free.”

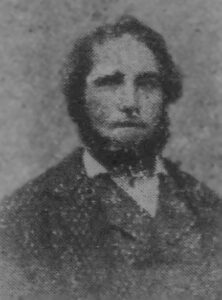

Stephen Turner

Another ancestor and brother-in-law to Forrester, Stephen Turner was already a well-established business and sporting man (he would become one of the first men of color to play the sport of Curling) living with his family in Portage, Wisconsin. Turner’s sister Narcissa Turner had married Richard Forrester of Richmond and both Forrester and Turner families had lived together in Richmond before Stephen relocated his family permanently to Wisconsin in 1858.

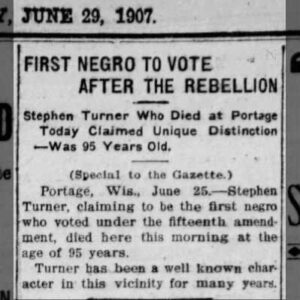

Wisconsin, through a popular vote, would extend voting rights to free men of color in 1849, but it was Stephen Turner with the support of his white neighbors who would register and vote in November 1860 election, making  him one of the earliest men of color to vote even before the ratification of the 15th Amendment. Turner would go on to vote every year until his death at age 96 in 1907. He would also become politically active in Wisconsin helping to form the Colored State Civil Rights Association acting as Second Vice President in 1889.

him one of the earliest men of color to vote even before the ratification of the 15th Amendment. Turner would go on to vote every year until his death at age 96 in 1907. He would also become politically active in Wisconsin helping to form the Colored State Civil Rights Association acting as Second Vice President in 1889.

For all Americans, voting is a fundamental right that enables us to uphold an open, honest and representative government. For African heritage Americans, voting has been a hard fought right that has been systematically disrupted and taken away by those who would deny the most basic right of all citizens in a democracy. As we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the landmark enactment of the 15th Amendment, we should remember those persons of color who fought and suffered for the voting rights we have in the present day – and honor them by exercising our right to vote. As we head into the 2020 elections, we would all do well to remember the deeds of men like Richard Forrester and Steven Turner who understood then what we should not take for granted today, that OUR Votes Matter.

- Saving Old Glory - March 31, 2023

- Keith Stokes receives Outstanding Achievement in Leadership Award - December 22, 2022

- Harriet Jacobs - December 22, 2022

Click on image to view pdf

Click on image to view pdf

Leave a Reply