RHODE ISLAND BLACK HISTORY ONLINE – For the RI Black Heritage Society

While much of African heritage historical research and interpretation regarding the 19th and early 20th centuries “Back to Africa” movement has focused largely on the efforts of the American Colonization Society or the Pan-Africanism effort of Marcus Garvey in the 1920’s, few know the earliest African heritage sponsored and organized efforts to return African people of the Diaspora back to their ancestral lands originated during the late 18th century in Newport, Rhode Island.

The American Colonization Society is history’s most prominent organization to support the return of free African Americans to what was considered greater freedom in Africa. The Society also helped to settle the colony of Liberia in 1821 during the Presidency of James Monroe, whose capital, Monrovia, is named in his honor. But the white elite of early America had less of an interest in returning Africans back to the place they were illicitly taken, but more as a means to reduce the real and perceived threat of the fast-growing population of free Africans in early America. In the minds of most whites during the early part of the 19th century, free African Americans would either compete for jobs with newly arriving immigrants in the cities of the North and or instill insurrection with the enslaved on the plantations of the South. The conventional reasoning at the time supported the concept; by returning free African Americans back to Africa, America would remove the growing economic threat along with the moral guilt of former enslaved.

Unlike the economic thinking of the American Colonization Society, there was an earlier movement whose reasoning was more of a religious nature. Perhaps the first effort in America to attempt both a religious conversion coupled with settlement in Africa was through the efforts of Rev. Samuel Hopkins of Newport. In 1774, Hopkins would lead the effort of sending the first two Africans to college for the purposes of training them as missionaries to be sent to Africa to convert natives and pave the way for further colonization by free Africans in America. Interestingly, Hopkins would share his plans with Grandville Sharpe, who would later become the leader of the effort to colonize Sierra Leone. Although Hopkins did select two men and sent them to be educated at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), the American Revolution interrupted those plans. Among the several African men that Hopkins originally considered, two were a young Salmar Nubia and Newport Gardner. These two men were prominent in later fulfilling the Rev. Hopkins original intentions.

In 1780, in Newport, Rhode Island, at the time one of Colonial America’s most active slave ports, a group of African men came together to organize and charter the Free African Union Society. As the first African mutual aid society in America, the Society’s lofty mission included monetary support for African families in financial need, a burial society to ensure proper interments, education of its youth, setting moral and religious standards for its members in the larger community and most importantly, raising consciousness and funds within the African community to someday return to Africa.

In 1780, in Newport, Rhode Island, at the time one of Colonial America’s most active slave ports, a group of African men came together to organize and charter the Free African Union Society. As the first African mutual aid society in America, the Society’s lofty mission included monetary support for African families in financial need, a burial society to ensure proper interments, education of its youth, setting moral and religious standards for its members in the larger community and most importantly, raising consciousness and funds within the African community to someday return to Africa.

The most significant difference between the back to Africa efforts of the Newport led African Union Society as compared to the white led American Colonization Society; Africans in America believed their full socioeconomic futures would best be realized with returning to their ancestral homes, while whites believed the socioeconomic future of America would best be realized with removing free Africans from the new and expanding nation, without concern for the Africans themselves. On January 24, 1787, Society President Anthony Taylor wrote a letter to early American abolitionist William Thornton detailing the Society’s interest in raising funds to establish a free African colony in Africa stating:

Sir, our earnest desire of returning to Africa and settling there has induced us further to trouble you with these lines, in order to convey to your mind a more particular and fuller idea of our proposal, agreeable to the Articles heretofore agreed upon by the Union Society. We want to know by what right or tenor we shall possess said Lands, when we settle upon them, for we should think it not safe, and unwise for us to go and settle on Lands in Africa unless the right and fee of the Land is first firmly, and in proper form, made over to us, and to our Heirs or Children.

On January 4th, 1826 sailing on the vessel “Vine,” Deacons of the newly organized Union Colored Congregational Church of Newport, Okyerema Mireku (aka Newport Gardner) and Salmar Nubia (aka Jack Mason), two of the original founders of the African Union Society, and at the advanced ages of eighty and seventy, left Boston harbor with thirty additional Africans from their Newport congregation to establish a colony in Liberia. As the group was ready to set sail, Deacon Mireku proclaimed:

I go to set an example to the youth of my race. I go to encourage the young. They can never be elevated here. I have tried it sixty years, in vain. Could I by my example lead them to set sail, and I die the next day, I should be satisfied.

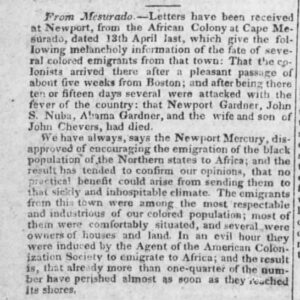

They arrived on February 6th to great welcome and fanfare, but as many as a quarter of the party (including Mireku and Nubia) succumb to fever and died within a year. Triumphantly, they had not died in a land where men were held as slaves. They died free in their own land.

They arrived on February 6th to great welcome and fanfare, but as many as a quarter of the party (including Mireku and Nubia) succumb to fever and died within a year. Triumphantly, they had not died in a land where men were held as slaves. They died free in their own land.

- Saving Old Glory - March 31, 2023

- Keith Stokes receives Outstanding Achievement in Leadership Award - December 22, 2022

- Harriet Jacobs - December 22, 2022

Click on image to view pdf

Click on image to view pdf

Leave a Reply