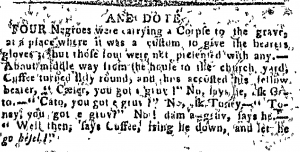

Anecdote

FOUR Negros were carrying a Corpse to the grave at a place where it was a custom to give the pall bearers gloves: but the four were not presented with any. About middle way to the church yard, Cuffee turned around and accused his fellow bearer, “Caesar, you got gloves.” No, go ask Cato. “Cato, you got gloves.” No, ask Toney. “Toney, you got e gloves?” No! dam have gloves says he. “Well then, says Cuffee, lie down, and let he go himself.”

In Colonial times, death was a very common occurrence reaching into all families regardless of wealth, social station and race. In seaport towns like Newport, Rhode Island, influenza, scarlet fever, and smallpox ravaged the population as frequently as ships would drop anchor with infected passengers and cargo arriving from the far regions of the known world. At the time, epidemics accounted for many of the deaths–sweeping young and old away in short order. With the frequency of deaths, funerals and proper burial measures became an important routine of the living.

The Newport Mercury newspaper on September 9, 1794 ran what might have been an amusing story for white readers simply entitled, “Anecdote.” The story, making light of the lack of order and solemn tradition within an African funeral, provides a humorous account of four African pall bearers preparing to take a recently departed fellow person of color to their final resting place. While the story is typical of the stereotypical views most whites held at the time, it was far from being even remotely accurate in its description of how the African community of Newport placed special efforts to provide for the proper burial of its members.

The regulation of the African Union Society at the Funeral of any of their departed brethren.

1. The notice shall be given to all the members by the sexton or by some other member who shall be chosen for that purpose to warn all brethren of such Death and the time such an one to be buried.

2. One shall be chosen to regulate and order the movement of the procession to the Grave.

The Procession to the Grave

3. The Sheriff shall proceed alone before all then follow two and all the members of the brethren

4. The Clerk of the Committee shall follow alone, who shall proceed the committee. If they have no Clerk, the last man in committee shall proceed.

5. The Secretary of the Society shall proceed the counsellors alone and the two presidents follow the last of the members.

Return from the Grave

6. The President shall proceed and all members follow and the sheriff follow the last of all.

– African Union Society Meeting January 14, 1790

While the funerals and burials of the white population were overseen by the houses of worship, Africans would turn to themselves to properly manage the affairs of their own departed. In 1780, a group of African men came together in Newport to organize and charter America’s first African mutual aid society known as the Free African Union Society. The Society’s lofty mission included establishing a burial society (Palls and Biers) to ensure proper funerals and burials for the larger African community. In 1790, the Society promulgated a set of regulations to oversee proper burials that included both the procession to the cemetery and the proper participation of the community. In an African funeral in Newport, the leaders of the African Union Society would lead the procession with the body on a wagon from the center of the town to the burying grounds. The procession would be organized by a ceremonial sheriff or undertaker, a well-respected position within the African community. Once buried, the procession would return for a time of reflection and celebration of the dearly departed’s journey home.

It was once very famously said, “History is written by the victors,” and regrettably, the voices of the oppressed is sometimes lost to the ages. Fortunately, here in Newport, Rhode Island we have a large repository of primary source materials including diaries, letters, wills and even the minutes of an African Union Society to tell us something about our early American heritage that is much more accurate, relevant and revealing about how Africans lived, worked worshiped and even died in Colonial America.

-KS

- Saving Old Glory - March 31, 2023

- Keith Stokes receives Outstanding Achievement in Leadership Award - December 22, 2022

- Harriet Jacobs - December 22, 2022

Click on image to view pdf

Click on image to view pdf

Leave a Reply