Part One

Over the next few months, I’ll be embarking on a journey to the places of my ancestral history – first stop – Jamaica, West Indies. This trip will be highlighted with me, as the direct descendant of an enslaved Jamaican, meeting with the direct descendant of my ancestor’s European enslaver at the very plantation for the first time in 221 years.

As we have done with other branches of my family tree, we have traced the generations of my maternal grandfather, George Nicholas Barclay, back from his adult life in Newport, Rhode Island, his childhood in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on through his father’s life in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and found my great, great grandfather, Robert Barclay. In doing so, we have uncovered a story that reveals the journey from enslavement to freedom; a story so unique – yet so very American.

America is a nation built on the ideals of personal freedom, equality and opportunity for all, but the one chapter in our country’s storied past that has run counter to these lofty principles has been the legacy of enslavement of Americans of African heritage.

Being New England born and raised in Newport, one of the country’s most historic cities, I have always wrestled with my own internal conflict with the historical paradox of an America that is the birthplace of civil liberties, religious freedom and democracy, yet also birthed a centuries long struggle of enslavement for an American people with my shared African heritage. This is a complex birthright highlighted by both human bondage and freedom, and one that has my own family origins directly tied to one of history’s most important emancipation and reparation efforts – joining together the most active nations within the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade between West Africa, Great Britain, Jamaica and America.

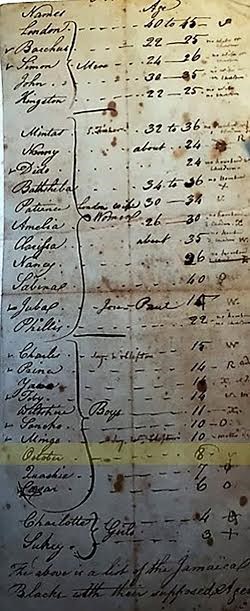

David Barclay’ 1801 Account of Emancipation

My family story starts with a wealthy English merchant David Barclay, a prominent supporter of Abolitionist William Wilberforce, and recognized today as a founder of Barclay’s Bank. Around 1787 he acquired through a settlement of a debt a grazing plantation in Jamaica called Unity Valley Pen – along with nearly thirty enslaved African-Jamaicans. A Quaker, Barclay had long family ties with Philadelphia and its Quaker community dating back to his great grandfather, Robert Barclay, a contemporary of William Penn and who had authored in 1696 “An Apology for the True Christian Divinity” that would define the essence of the Quaker belief system. As a staunch Quaker and Abolitionist, Barclay abhorred the idea of being a slave owner, and ordered their emancipation. With the fear of an uprising a constant on the island, free Africans would have no hope of making a living, or even surviving. So Barclay went one step further. He developed a plan to provide for a form of reparations – for the personal suffering placed upon them by the owner class of Europe and the Americas.

At the direction of Barclay, his agents in Jamaica transported the African emancipates to Philadelphia. These newly freed Africans, many of them children, arrived on July 22, 1795. Barclay chose Philadelphia because he had long business interests there before the Revolutionary War and through his friendship with Benjamin Franklin, he became well acquainted with the Quaker abolitionists’ activities in the American city. Philadelphia at the time also had the largest free African Heritage population in the Western Hemisphere. Possibly the one place a newly freed people could not only survive, but prosper.

In the year 1795, Philadelphia was the young nation’s second largest city and the nation’s capital, home to our first President, George Washington. Enslaved Africans had been an integral part of the “City of Brotherly Love” since the 17th century, many coming from the African continent by way of the West Indies. But in 1795 the twenty-eight recently emancipated Africans from Jamaica would begin a highly uncommon journey towards freedom; a story that few in Philadelphia or the nation would know until now.

The group was placed in the care of the Quaker Society aptly called, the “Pennsylvania Society for the Improvement of the Conditions of Free Blacks.” They were initially clothed and cared for through Rev. Richard Allen at the recently formed Mother Bethel AME Church. There are also reports that Rev. Absalom Jones of the St. Thomas African Episcopal Church also provided aid and shelter. St. Thomas is the first African Episcopal Church in America founded in 1792. Mother Bethel is the first African American AME Church in America founded in 1794. Each of the newly emancipated were set up in a trade skill, many as indentured servants with members of the Quaker community. David Barclay asked for reports of their well-being, and would even leave some money for them as part of his will in 1809.

1795 Inventory of the emancipated Jamaicans in Philadelphia including October. Image courtesy of the Pennsylvania Historical Society

One of the youngest members of the new arrivals is a boy of eight named October. Upon his arrival to Philadelphia he is renamed Robert Barclay, carrying the same historic name of one of the early members of the Quaker faith. That boy of eight, arriving as a stranger in a strange land, is my great, great grandfather. Young Robert is indentured for thirteen years as a “Windsor Chair Maker” with a John Chapman. Chapman is a master chair maker and active officer in the Arch Street Quaker Meeting House. By 1808, Chapman is listed as a cabinet maker and over the next few years, Robert Barclay is listed alternatively as cabinet maker and painter.

As I continue the next chapter in this journey, I will share Robert Barclay’s life in Philadelphia, growing up as a free man of color in the Antebellum period as he and family members become actively involved in the evolution of America’s earliest Black church, civic, educational and abolitionist organizations.

What I’m learning on this journey is that the Black Lives Matter movement of today affirms African heritage presence and contributions to America, just as the story of my Barclay family reiterates that Black Lives have always mattered.

- Saving Old Glory - March 31, 2023

- Keith Stokes receives Outstanding Achievement in Leadership Award - December 22, 2022

- Harriet Jacobs - December 22, 2022

Click on image to view pdf

Click on image to view pdf

December 19, 2022 at 11:36 pm

Many civilizations advanced as they moved, but many African civilizations were decimated because because they were MOVED into diaspora. In genealogy, the study of African ancestry is uncovering this human tragedy. I’d be interested in published studies on point looking at what the paths fr US East Coast-Caribbean slave trade tell us abt the civilizations decimated by slavery trade.

December 21, 2022 at 7:51 pm

Michael,

Thank you for the comments and we at 1696 are inspired to connect these stories. If you want to schedule a consultation we certainly can provide you additional resources. Please contact Keith Stokes keithnpt@gmail.com directly regarding your inquiry.

1696 group